PT 1.

Jon James Uncategorized 3 Comments 1 MinuteEdit

Twix wrapper – 30th September 2022.

My sense of continental geography, or even just French geography is poor. I had driven for eight or so hours, more or less following the magic thread of the sat Nav. I knew I was somewhere central-southish, but exactly where, and in relation to what I really couldn’t say.

It had been the same before we left. Where are you going? People had asked. Well I’m not really sure was my rather embarrassed answer.

The journey itself had been impressionistic. Driving through hours of night. Getting lost in industrial Rouen. Waking to a beautiful mediaeval town and sampling early morning coffee and coissants. Fields of sunflowers. Flat lands bounded by curtains of grey storm clouds, split by repeated lightnings.

The mediaeval town had not been an exception, there were more, and the odd fairytale chateau. Building developments seemed much less obvious, or non existent. How was this? What is different about French population dynamics compared with those of England, where every square inch seems to be being developed for housing?

The countryside appeared well tended and attractive. Healthy trees with clean trunks to above traffic height, rather than lorry-pruned as often seems to be the case here. Free parking and even special overnight provision everywhere. Welcoming! Fresh bread and cheese that seemed to feed the soul as well as the stomach. Was this somehow the result of putting people first? The French resistance to erosion of working practices and worker’s rights. It seemed to fit, but I am probably wrong; silly to presume to pronounce on a country after such a short time, but that was the impression.

Finally, arrival and a few days with the friends whose generosity had allowed this holiday opportunity, before being left to ourselves to recoup from a difficult summer.

So now, a few days in and a chance to look at the atlas and find out where we were. Availles Limosan, a bit west of central. The drive had crossed the Loire valley – ah, that explains the beauty. I turned over the page, so we are near Limoges. Porcelain if I remember correctly. Maybe a destination for a day out. Then I notice the colouration of the map indicating rising ground to the east. I turn another page or two drawn by the lure of mountains. And then, for the first time, it really dawns on me; I am on the continent! Connected to all that extraordinary scenery, culture and history.

Old patterns of thought and obsessions kick in. Switzerland. I could get to Switzerland. Why didn’t we come for longer!

Switzerland is a powerful draw to my imagination. Why? A constellation of reasons. The most wonderful scenery; recollections of walking holidays in the Alps, walking on grass (I am no climber), but high up and looking across to valleys of snow and rock; to the Eiger and the Matterhorn. A night of fireflies during a walk towards Italy through the Ticeno on a holiday way back in university days. And then there is the science; Einstein and CERN. CERN on the French Swiss border, the world’s largest particle accelerator and a Mecca for physicists. And Einstein, living in Zurich in the early days before his time in Berlin and the rise of narzism, sailing on the Zurichsee and thinking of light and relativity.

So, two good reasons for being drawn to Switzerland, but not the key reason. The key reason, perhaps strangely, is that the pioneering psychologist Carl Gustav Jung lived in Zurich. Why is this important? I find it hard to say. I read Jung’s collaborative biography, ‘Memories, Dreams, Reflections’ more than forty years ago, along with various other books about him, or in which he was discussed, but I was by no means a careful or particularly avid reader and certainly no Jung scholar.

But something of his writing and the life and thought he described has penetrated deeply and lodged within. Only fitting, I suppose, that work by Jung should should find its way into the unconscious.

There are two physical foci to this obsession, the first, simply enough, is Jung’s house in Zurich, or, to be more precise, in Kusnach, a region of Zurich on the shores of the Zurichsee. 228 seestrasse if I remember correctly. The second and more powerful, is Jung’s retreat at Bollingen, further up the lake.

Bollingen was built in stages; in some sense a physical manifestation of the psychologist’s thought and development. I think I remember reading that Jung felt himself to be most at home when at Bollingen, surrounded by the natural world, performing the simple routines of cooking and firewood collection, on the lapping edge of the zurichsee.

I have been to Zurich twice and both times felt obliged to act on my obsession. The first evening of my first trip I vainly tried to find the Bollingen retreat. This was a long time ago, well before the days of the internet and easy information gathering, and the effort was a complete failure. All I have, somewhere, is a grainy twilight photograph of some faintly towered building – nothing to do with Bollingen. However the next morning I walked along the seestrasse in Kasnach to number 228, Jung’s House.

I remember standing at the gate, looking down the long path to the front door. Then, as I took my obligatory photo, a man, the occupant I assume, walked up the drive and greeted me at the gate with a ‘good morning’ and a ‘can I help you?’ . Being an idiot, and shy, I mumbled a ‘good morning’ and a ‘no thank you’ and walked on. I don’t know for sure, but I think at the time Jung’s grandson and family were living in the house and I often wonder if, recognising me for the pilgrim I was, he might have stayed to talk or even offered to show me around.

My other memory of this incident is in some way stranger but perhaps more telling. I remember that, as I approached the house, I was actually shocked to see, first a petrol station (Texaco I think it was, in a garish bright red) and then, of all things, a Twix wrapper lying in the gutter, right outside the house! Shocking, as I’m sure you will agree! Why? Well, can you imagine, just the absolute prosaic mundanity of it. What had I expected? I’m not sure. Not maybe to meet the spirit of Jung, or the archetypal figure of Philemon, with his kingfisher wings, strolling the garden or leaning on the front gate, but at least some sanctity, or sense of the numinous – certainly not a petrol station and a Twix wrapper!

Of course, this was all a long time ago, so I might be tempted to lay such infatuations at the door of youthful folly, however this would be disingenuous as I was gripped by similar feelings just a few years ago. I was on a work trip with a PhD student. We were at the Paul Sherrer Institute (PSI) just outside Zurich. The experiment we were conducting (developing a method for combining neutron and x-ray imaging techniques) was intensive, but there was some free time and I decided to have another go at finding Bollingen.

I set off along the lake again and this time I nearly made it. All the way to Raperswill, the region of Bollingen. But somehow I had put the dot on the map in the wrong place and I wandered around missing Bollingen by a mere mile or so. I have wondered since if something inside me was sabotaging my attempts to visit this place, but more likely it was just a combination of rush and natural incompetence.

Anyway, not to worry! I have a better plan now! I’m going to hire a dinghy in Zurich and sail to Bollingen. What better way to get there? To sail the water that Einstein and Jung sailed – the length of the lake to the tower – wouldn’t that be a thing to do with a day.

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 5 MinutesEdit”Twix wrapper – 30th September 2022.”

Anyone for rockpooling? – 27th August 2022

A short blog with a difference.

I have been doing some work with nature charities, surveying rockpools in order to monitor variety and abundance of marine species (more details here). As part of this ‘work’ I am experimenting with high resolution zoomable photo-mosaics as a means of recording rockpools, but also, maybe, as a teaching/fun resource.

By clicking/tapping on this image, and zooming into the photo-mosaic that replaces it, and panning around, you can explore your very own rockpool.

Best results are with an at least reasonably high resolution screen and an not too slow internet connection. (Please let me know of any difficulties with using this, or indeed, thoughts in general).

There are three types of sea anemone in this pool, one very easy to spot, the other two are a little harder.

(I may try to add a recording of shore sounds that plays while the image is open at some future date.)

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 1 MinuteEdit”Anyone for rockpooling? – 27th August 2022″

Rock – 7th August 2022

(After a very difficult few weeks, helping look after a relative suffering the last stages of cancer. )

I don’t want to write for a few minutes, but rather sit here and soak in the peace.

It has been too long. I am too tired to think.

I breath in the cool damp air, close my eyes, open them again and look to the sea.

A small flock of pipits rise and caught by the breeze arc away towards the hill. They are an analogy for something within, but I can’t put my finger on what.

The last time I came here this place was all wrong. Cold and bleak. Now it feels like life. Like breath. I would dissolve and seep into these rocks. Here. Forever. I have thought about this before, to be a rock on this hill. The calm being of it. Warm and chill. Rain tears on stone skin. Night sky. Day sky. Skylarks. A peregrine’s cry. In the spring a bird’s nest, a wheatear or stonechat’s maybe, at my feet, or behind my stone ear.

Am I irritated that a place can change so radically, from the negativity of my last visit, to the adoration of this? If I am honest, yes, but ridiculously – do we expect the desert traveler and the drowning man to see the same river?

Jon James Uncategorized 1 Comment 1 MinuteEdit”Rock – 7th August 2022″

Gorgons

I live in a beautiful place. But enjoying it is like going for a walk in a garden in which lurk many gorgons. Glimpse any one of them and you will be turned instantly to stone.

Enjoy the sunny days, but don’t think about climate change. Explore the sea but don’t think about the plastic pollution. Enjoy the sound of the river outside the door, forgetting how it flooded you that time and will surely do so again. Photograph the extraordinary wildlife, but keep out of focus its continually reported decline. Enjoy the woods on the valley sides but try not to see the bare branches of the dead ash.

So many lurking gorga, you need to walk wearing blinkers.

But still there is so much that is beautiful.

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 1 MinuteEdit”Gorgons”

Community

I took a trip to our nearest town a few days ago, to buy some groceries. It is a short drive, from the Cych valley, up and over, to the broader valley of the Teifi. A pleasant route along largely single-track roads between high banks covered in, depending on the month, snowdrops, primroses, daffodils, bluebells, wild garlic or foxgloves. The journey is something of a mild roller coaster, with the last few miles, once you start dropping down toward the river, reminding me of coming into land in a aeroplane. The slow descent, the engine quiet, coasting, occasional course corrections, and short bursts of power to momentarily recover height, even the turbulence of bumps in the road, all add to the illusion. Then, finally, a moment of stillness, before re-joining the world of people and purposeful activity.

The ostensible purpose of the trip, to buy the groceries, was soon completed by a few minutes shopping in CK’s supermarket. CK’s is the older supermarket in the town. The staff, some young and some older are generally cheerful and I much prefer it to the shiny new Co-op with its loathsome automatic checkouts.

My shopping done the real point of the journey could be indulged in; a coffee in the Cwtch cafe in the high street. The Cwtch is one of the scruffier cafes in Emlyn, but the coffee is good, and, best of all, both the cup and milk start off good and hot and so the coffee can be enjoyed over half an hour or so, even if sat outside with a book, as I usually am. Being a regular customer, I have earned the greeting of ‘the usual’ when I arrive, which is an additional small pleasure.

I enjoy these little excursions; a pleasant change of scenery and the feeling of people around me after the quiet and sometimes enclosing atmosphere of the Cych. The little town is, of course, struggling, but today was Thursday, which is cattle market day, and so the car park and high street were busier than usual with the local farmers, with their 4 by 4s and trailers. I do not want to get into the pros and cons of vegetarianism, but, albeit unthinkingly, I enjoy the presence of the cattle market in the heart of this little town. The sounds and sights it brings, the business and the feeling of purpose and connection with broader community. Not new or original observations maybe, but real to me.

This feeling of community has been a new thing for me. I have been living here for coming up four years now, but its novelty has not worn off. It was not anticipated, though the friendliness of the people, as experienced on various trips and holidays, had always made an impression and was one of the chief reasons for moving here.

I think I hadn’t known I was missing the ‘community thing’ until I experience it. I have been lucky in the past, nearly always living in attractive places, and hardly meeting anyone who was actively unpleasant, but this is different. It is hard to pin down, but I characterise it to myself as a change of emphasis in human interaction. Here, whenever you meet someone, in whatever capacity, you seem to meet the person first and the role they occupy second. There is an immediacy and a human touch to the contact, which, in turn, seems to bring about a corresponding openness and relaxation in me. I find myself chatting in a way I never did while in England.

As I sit, reading, looking around, I enjoy the snatches of Welsh that come my way from people talking in the street. The Welsh language is supported at government level; not just taught within state schools, but actually prescribed as the language of teaching.

Because I enjoy it, I fear the loss of this local feel and culture. It is so vulnerable. Already areas I visit in Pembrokshire are becoming anglicised. One little community that lies at the end of a favourite walk of mine, made the news the other day for being, I think it was, 95 percent holiday homes. This area is not so honey-potish and so may be slower to change but I would hate to see this special quality go.

Of course, as an incomer myself, I am, to some extent, an agent of the very change I fear. But then maybe there is more than one way of incoming to a place. I hope I come with respect and humility and an appreciation of what is here.

It is soon time to head back. It has recently rained and I catch glimpses of the distant Preselis through gaps in the high hedges as they catch the sun and look bright in the clean air. I realize again how beautiful they are and how lucky I am to have ended up here and what a huge opportunity it presents. But how do I express all that I would like to express? Time is short I know, which begins to add impetus, but still, I have no real idea.

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 3 MinutesEdit”Community”

Keep swimming!

The somewhat fuzzy photograph above, was taken, in a rush, at the end of a rockpool survey. Looking at it back at home it wasn’t at all obvious to me what it was, or even that its subject was organic. More geological perhaps? Some sort of crystal growth maybe? A cluster of stars on a piece of rock at the bottom of a rockpool.

I would normally have reached for reference books or the internet to identify a new find, but this time I didn’t know where to start, so I took the easy route and appealed to Twitter, hoping one of the several expert rockpoolers I know to be online would get back with an identification. And, within a few minutes they did1.. Not geological but biological. Animal in fact. A specie of sea-squirt commonly known as Star Ascidian. Hence the stars, of course.

I was pleased. A new entry for my growing rollcall of species found in the pools of this little north Pembrokeshire Bay2.. I looked up Star Ascidian online to get the proper scientific name and its scientific classification:

Common name: Star Ascidian

Scientific Name: Botryllus schlosseri

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Tunicata

Class: Ascidiacea

Order: Stolidobranchia

Family: Styelidae

Genus: Botryllus

I like these scientific names and classifications. I enjoy the feeling of learning and arcane knowledge they project. They conjure images of ranks 18th and 19th century amateur scientists grappling to understand the world around them, at a time when the balance between knowledge and mystery left room for such intellectual curiosity and simple enthusiasm. The problem is they pique my interest. Like tips of icebergs, they hint at more below; hidden research, information and knowledge. I find I need to delve further, and that one thing leads to another, so that what might have started as a chance finding of something curious in a rockpool, all too easily mushrooms into a much larger, sometimes even burdensome, investigation.

Whenever I sense this process starting, I am reminded of J.R.R. Tolkien’s beautiful short story ‘Leaf, by Niggle’, in which an artist, Niggle, becomes obsessively absorbed in a particular painting which seems to take on a life of its own.

“There was one picture in particular which bothered him [Niggle]. It had begun with a leaf caught in the wind, and it became a tree; and the tree grew, sending out innumerable branches, and thrusting out the most fantastic roots. Strange birds came and settled on the twigs and had to be attended to. Then all round the Tree, and behind it, through the gaps in the leaves and boughs, a country began to open out; and there were glimpses of a forest marching over the land, and of mountains tipped with snow. Niggle lost interest in his other pictures; or else he took them and tacked them on to the edges of his great picture. Soon the canvas became so large that he had to get a ladder; and he ran up and down it, putting in a touch here, and rubbing out a patch there. When people came to call, he seemed polite enough, though he fiddled a little with the pencils on his desk. He listened to what they said, but underneath he was thinking all the time about his big canvas, in the tall shed that had been built for it out in his garden (on a plot where once he had grown potatoes). “

I particularly that last line ‘on a plot where once he had grown potatoes’, presumably illustrating how the obsessive work on the painting displaced more practically fruitful activity!

Anyway, my little sea-squirt acted, for a while, a little like Niggle’s Leaf. I have sketched one of the main branches of its tree here and will add one or two more in a second blog shortly.

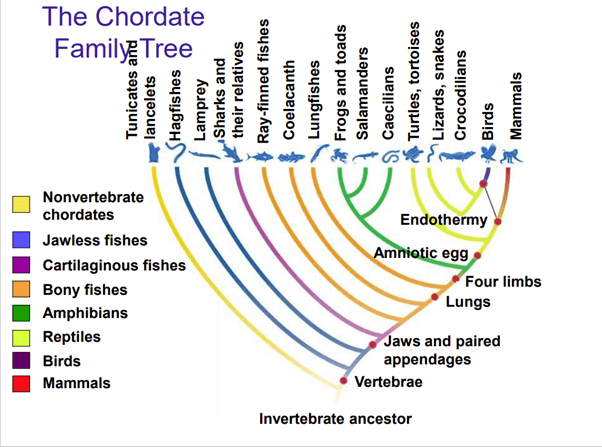

The first thing I noticed was that the sea-squirt belongs to the Phylum Chordata. The ‘chord’ in Chordata refers to a primitive nerve chord that may run along a creature and from which the spinal column and backbone evolved. Chordata is therefore the phylum to which all vertebrates, including ourselves belong.

Two things followed this; the first was I realised that although I had recorded many different species since I started delving into these rockpools, this was the first that belonged to this group. How different this is to the land-based animal life we are all familiar with, where Chordata seem so dominant. For example, all the mammals, including ourselves, amphibians, reptiles, birds, fish, snakes, lizards are all Chordata. I started to wonder why this difference is so marked, which led to reading read about disparate subjects such as why insects are small and how the average density of many animal bodies, including our own is almost the same as that of sea-water, which means that marine life doesn’t feel gravity in the way land animals do enabling the wonderful strange and delicate forms of rockpool life I had been finding.

Having learned that belonging to chordata implies a primitive spinal cord or backbone, I looked again at the photograph. It was not at all obvious how this thing, which appeared little more than a smear of patterned jelly, could have a backbone or indeed would have any use for one. Turning to the formal definition of Chordata I read,

“Chordata: A phylum of the animal kingdom comprising all the animals that have, at some stage in their life, a notochord (a hollow dorsal nerve cord), pharyngeal slits, and a muscular tail extending past the anus. Includes the subphyla Cephalochordata, Urochordata, and Vertebrata (vertebrates).3.

The clue is in the second line; “at some stage in their life”. It turns out that the sea-squirt starts out as a free-swimming larva, somewhat like a little tadpole, complete with a primitive, eye, tail and notochord and importantly, a very rudimentary brain, designated to controlling it’s motion.

After a brief free swimming (pelagic) period the tadpole attaches itself to a suitable substrate and metamorphoses into the attached (sessile) jelly form I found.

This life-cycle, of pelagic larva to sessile sea-squirt, turned out to be more significant than it at first seemed.

Evolutionarily speaking the story goes like this; Once Upon a Time (roughly 550 million years ago) there was a specie of tiny tadpole like creatures that spent their days swimming in the sea. Some of these tadpoles found that it took much less effort to cling to the rocks and wait for the food to come to them than to actively seek it out by swimming, while the others stuck with the original swimming about plan. Each group became somewhat set in their ways and slowly evolved to become more suited to their adopted lifestyles.

The group that stuck with the swimming, we could call them the pelagic group, went on to great things, or, even if we eschew this somewhat subject value judgement, at least went on to great variety and experimentation, as it is now believed, that these little free swimming tadpoles evolved to give rise to all the vertebrate life on earth, including, of course, ourselves.

Things did not go as well for the sessile group. Nature discovered (through the usual method of ruthless experimentation no doubt) that once attached to its rock the organism no longer needed its tail, eye, embryonic spinal cord and backbone, or, for that matter its brain. These organs the sea-squirt evolved, in a process known as regressive evolution, to digest for the sake their protean content!

The element of black humour in this coupling of an organism ‘settling down’ with the loss of its mental faculties, has not been missed. The philosopher of mind, Daniel Dennett, draws a parallel to the process of a university professor obtaining tenure!

“ The juvenile sea squirt wanders through the sea searching for a suitable rock or hunk of coral to cling to and make its home for life. For this task, it has a rudimentary nervous system. When it finds its spot and takes root, it doesn’t need its brain anymore so it eats it! (It’s rather like getting tenure.) ” 4.

Professor Sea Squirt5

Different lines of investigation, including modern genetic analysis, indicate that the sea-squirt is the immediate ancestor of all vertebrates and therefore is considerably closer to humans than many other forms of equally unlikely looking life. For this reason, among others, the sea-squirt has become the model organism for studying the evolution of vertebrates, including the origin and development of human hormone, nervous and immune systems. The latter, among other things, providing a new range of chemo-therapy drugs6..

The above is a tiny sample of what investigations of the humble sea-squirt have revealed and are still revealing, but already I somehow felt the need to shake its hand, if only it had one.

Evolution of chordates showing the sea-squirt (Tunicates) as the ancestor of the vertibrates.7.

- Thanks to: https://twitter.com/lynne08777205

- https://jonjamesart.com/shore-search/

- For example: https://www.biologyonline.com/dictionary/chordata

- MLA (7th ed.) Dennett, D C. Consciousness Explained. Boston: Little, Brown and Co, 1991.

- Drawing by Paul Jackson. ©Randel McCraw Helms, 2018

- https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2000/05/potent-cancer-drugs-made-sea-squirts-provide-recipe/

- https://www.paulding.k12.ga.us/cms/lib010/GA01903603/Centricity/Domain/2373/CHORDATES%20and%20Vertebrates.pdf

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 6 MinutesEdit”Keep swimming!”

Delays

A series of visits from family and friends are likely to stop me finding time to write anything for a while – the penalty for living in a beautiful place!

Hope to get back on it soon.

Jon

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 1 MinuteEdit”Delays”

Just one of those days

(I wouldn’t have bothered to blog this, but I have decided to be more inclusive and curate less. It is best treated as an observation in ‘over thinking’ and maybe an exercise in self-mockery! There maybe however one or two things perhaps worth picking up at a later date.)

Pt 1. (Carpark on the Preseli hills)

I have written several times below about the wonders of this place. The way the light transforms, the calm and the wildlife, the sculptural rocks and soft air. But, of course, it is not always like this. Grey days exist everywhere and for everyone and it is grey today. Today also the landscape matches the mood. I feel grey; my head frozen, locked up and useless. This is my least favourite state. Joy comes from freedom and freedom from thinking. But, for the last week or so, my head has been having none of it. In this frame of mind all the bad things seem real and the good things illusory, which is, of course, as it should be in a meaningless, random and uncaring universe!

Some of this mood is, I would say, objectively justifiable. I find myself obsessively typing ‘Ukraine news’ into Google, searching for reassurance, while scouring social media for a sense of contact and warmth. The first is nowhere to be found and the second scarce.

My project to write a book feels already dead. Killed by just the demons I suspected it would be killed by, but which I hoped to exorcise by calling out and naming. But no, they know me too well and are too clever and wily.

Of course, there is probably never a ‘right time’ to try and write a book, just as there is never a right-time to have children or move house, but this time, with global conflagration appearing a distinct possibility, makes even starting seem pointless.

The fact that I am not alone in this gloom is some comfort. Talking to a neighbour the other day black humour welled up when she said, ‘well I’m not buying any ripen-at-home fruit, or long-playing records for that matter at the moment!’ Not easy times for a perfectionist obsessional who wants everything to be just right, while simultaneously searching, with the aid of a very proficient imagination, for reasons for them not to be.

I have found retirement also brings challenges. The working week, with its cycle of pressure-relax-pressure-relax, used to at least act like a simple pump, keeping the stuff of life moving. Take that away and you can be left with stagnation and the opportunity for a real sharp-toothed-long-clawed existential crisis. I have always had a propensity for such crises, but with little to distract me, this talent can truly blossom.

I remember I chose science, specifically physics, as a career because I realised, I needed something challenging but, most importantly, something external and objective, to engage with. I knew, even by then, that if I didn’t distract the beast with some red meat, it would surely eat me alive.

I fancy others have felt similarly. Was Einstein referring to something similar when he said:

“Strenuous intellectual work and the study of God’s Nature are the angels that will lead me through all the troubles of this life with consolation, strength, and uncompromising rigor.”

Not many of us have the strength to forge our sense of meaning, Nietzsche-like, out of nothing, with just our bare hands. In any case, is it possible to hang meaning from something we have constructed ourselves? What other choice do we have? To hang meaning off God or Nature. But both of these it seems can be pulled down relatively easily. Perhaps recognition of our common human plight and compassion for other sufferers is at least a starting point, but this too can be picked apart philosophically if one really chooses to do so.

Philosophical ideas, particularly those around free-will, determinism and reductionism have always had the power to empty life of meaning. This is one of the difficulties I have with writing; everything that doesn’t tackle at least one of the three or four major philosophical questions of life and existence can seem like so much padding! Ridiculous to feel like this, I am sure. Maybe the answer is to simply stop thinking about such things and accept that, to quote Kirkegard; “Life Is Not A Problem To Be Solved, But A Reality To Be Experienced.”

Who knows! I am tired of swinging between imagined possibilities. I drove out here to write, but can’t and the weather does not inspire walking, so I am heading back home.

Pt 2. (Two hours later)

I dropped a hundred feet or so, from the relatively flat top of the hill, down the steep sided valley and the world changed. The mist thinned, making it to appear luminous rather than flat grey. The bluebells began to faintly glow from the verge and birds (pipits and a wheatear I think) could be seen moving along the banks on either side of the road. I was struck by the warmth of the air blowing gently through the van window.

The usual order of things was reversed. Usually, I love to get out of the valley. To the more open uplands. But not today. The terrain matched the mood. Enough of the bleak. Why would we choose to live on the colder, windier uplands when the shelter of the warm folded valley is nearby. To profess love of such bleakness, be it mountain or sea, is, it seems to me now, to not really know these places. We are not designed to live in such inhospitable environments, however good the views.

These thoughts and feelings recalled something I had read recently on twitter. An author I follow1. and who I suspect experiences similar days, had tweeted a quote from the writing of the Scottish philosopher David Hume;

[1] “The intense view of these manifold contradictions and imperfections in human reason has so wrought upon me, and heated my brain, that I am ready to reject all belief and reasoning, and can look upon no opinion even as more probable or likely than another. Where am I, or what? From what causes do I derive my existence, and to what condition shall I return? Whose favour shall I court, and whose anger must I dread? What beings surround me? and on whom have, I any influence, or who have any influence on me? I am confounded with all these questions, and begin to fancy myself in the most deplorable condition imaginable, invironed with the deepest darkness, and utterly deprived of the use of every member and faculty.

[2] Most fortunately it happens, that since reason is incapable of dispelling these clouds, nature herself suffices to that purpose, and cures me of this philosophical melancholy and delirium, either by relaxing this bent of mind, or by some avocation, and lively impression of my senses, which obliterate all these chimeras. I dine, I play a game of backgammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends; and when after three- or four-hours amusement, I would return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strained, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any farther.”2.

Of course, it is interesting that despite the healthier and more natural feelings Hume described in the second part of this excerpt, whatever it is that drives philosophers and others to ponder the sorts of questions they ponder, drove him, sooner or later, back to the ‘hills’!

- Caspar Henderson

- https://jacklynch.net/Texts/treatise.html

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 5 MinutesEdit”Just one of those days”

Time to try

I have been blathering away to myself, for quite a long time now, about trying to produce a larger piece of writing, maybe even a book. I realise that if I don’t do it now it will never happen. Of course, it probably wont happen anyway. More than likely I will get bogged down in the usual feelings of shifting perspectives and fractal complexity that tend to assail me whenever I try to focus on a specific objective. But at least I will have tried, and the next time the thought; ‘it would be fun to write a book’ occurs to me I will be able to say, ‘remember, you tried that once and couldn’t do it’, so shut up and get on with something useful’.

So I intend to try. I don’t know what the usual or best approach is, but, given a rough direction, I intend to just start to write and simply see what happens. Sometimes thoughts breed thoughts in a way that makes planning too far ahead pointless.

So, I have put the first draft of a few paragraphs below, as a merest toe in the water and indication of intent! I may occasionally add little bits as things go along, if they go along, as I feel it will help me to put something ‘out there’. If anybody reads this and has comments, please feel free!

Preface

The rockpool is about a metre long, half metre wide and thirty centimetres deep. A small depression in dark rock lying at the eastern end of a small sandy bay on the north Pembrokeshire coast. I have arrived at nearly the lowest point of a low Spring tide. The sea is less than a meter above what is known to sailors as LAT or the ‘lowest astronomical tide’ and at such a tide much more foreshore is accessible than is usually the case.

It is cold and grey. The sea is rough from a recent storm, and a residual swell is washing round the headland that defines this side of the bay. Despite this cold greyness I can already feel the calming and soothing effect of this place working on me.

I have been visiting this Bay, and the particular area around this rockpool for a year or so now. I started coming here as part of a citizen science project designed to monitor species of shore life, but unfortunately, despite having worked in science for many years I found I lacked the discipline to do the science properly. I could not focus. So, instead of conducting proper timed searches I just potter about seeing what I can find and thinking and dreaming about the sort of things being near the sea makes you think and dream about.

There is much to inspire here. In terms of the wildlife alone it can feel like living inside one of those iconic ladybird books of the 1950s and 60s. A new edition maybe; ‘What to look for in Pembrokeshire’ whose cover would show an anemone filled rock pool and behind which dolphins would swim in a blue sea whith black fingered, red beaked Choughs displaying above. In these days of constant reporting of ecological disaster, I am drawn to this place as an iron filing to a magnet.

But it is not just the wildlife. The folded cliffs and the rocky outcrops that crest the nearby Preseli hills speak of geological drama and even the night sky appears clearer than usual, revealing worlds beyond.

Just wandering and experiencing is enjoyable here. Walking along the cliffs, or on the hills, is often dramatically beautiful. There is a quality to the light which, combined with the juxtaposition of sea, cliffs and hills produces something which is nearly always special and sometimes feels transformational.

Unfortunately, for me, it is never quite enough to just be in a place and enjoy it. I always want to do something more with it. Sometimes it is just to use it as inspiration for trying to paint or draw, or write poetry, but more often it acts as a spur to think about what I suppose might be thought of as the bigger questions of life, science and philosophy.

And so today I am sat here, on these rocks looking out to sea, with a coffee in hand wondering where to start.

But then I realise, it doesn’t matter too much where one starts. It is all connected. The sea is boundless. Wherever you jump in is, in some sense, the same as everywhere else. So, as I am in the fortunate position of having no plan to work to, no deadline and no one to please, I will probably just wander and see what turns up.

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 3 MinutesEdit”Time to try”

Short walk

I wanted to do a blog with no (or very few) words. Words can be so difficult; always limited or limiting in some way.

So here it is; a short walk in my favourite area of the Preselis – to share.

(The music is me attempting to play Roy Harper’s lovely instrumental ‘Blackpool’).

There is a little lyric with this song which I wasn’t up to singing:

"The rain falls like diamonds pin-pricks the still water spreadeagles it's laughter across the green sheet of the sleeping sea." Roy Harper - Blackpool, (from 'The Sophisticated beggar'). (Lots of good songs on this album, but maybe an acquired taste!)

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 1 MinuteEdit”Short walk”

Low tide

5th December 2021

I arrived at Pwllgwaelod bay entirely serendipitously near the bottom of a very low spring tide. Storm Arwen had come through a few days before and it was still grey, windy and cold with a considerable swell rolling into the eastern lee of the bay.

I had meant to just walk over the sand to the sea’s edge, say hello to the sea, and then head up the cliffs for my usual walk around Dinas Head. But, looking over to the far side of the bay, I saw the extreme low tide had left a little cove, which I particularly like, accessible without the usual scramble over wet rocks.

I wandered toward, and then around the headland that separates the two coves and made my way over the dark volcanic sand to the sea. There was nothing in particular to attract attention. I had seen seal pups here in the past, but there were none today. There was a pipit or two, the odd gull and a few crows flying dark against the grey sea, but no choughs, though again I had seen them here previously. Having nothing to engage with I simply stood for while gazing out to the horizon. It was when my eyes dropped that I noticed something in the sand, at my feet.

Even without its romantic and mythical connotations it was an intrinsically exciting shape. Had it been an exhibit in an art gallery, I can imagine the blurb would have used phrases like ‘dynamic rhythm’ and ‘tension of contrasting forms’. It was smooth, a fawn rectangle, gently rounded and swollen, with tightly coiled twisting fibres springing from both corners of one end; it reminded me of an element in a painting by Wassily Kandinsky.

It was a nice find and something new to add to the impressive list of species I have found in the few hundred square yards of this Bay1. It was, however, somehow something more. For a couple of days I had had Tim Buckley’s haunting ‘Song to the siren’2 going through my head, including as I had stood looking out to sea. And then there this was, at my feet, a mermaid’s purse . It seemed to be a small nod, outside of rational thought, towards the existence of meaning in the world: an act of synchronicity, and I must say, at that moment, welcome.

Jon

Notes:

- There is a photo record of species found in this little bay here: https://jonjamesart.com/shore-search/

- My favourite version: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JQZ5_3s4ltU&list=RDJQZ5_3s4ltU&start_radio=1

- Also known as a dogfish. Scientific name: Scyliorhinus canicula. More details here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Small-spotted_catshark

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 2 MinutesEdit”Low tide”

Twenty four hours (or so) on the Preseli hills

18 November 2021

I find this place on the edge of the Preseli hills has everything I need. There are the hills, a large expanse of sea and an even larger expanse of sky.

I usually arrive late afternoon, perhaps after a walk around Dinas Island and then sit peacefully as the world quietens. I walk up to the rocks at Carn Enoch before it gets dark and in the morning cook and eat breakfast, sit and drink coffee, read and daydream or maybe try to write. Sometimes I will go for a walk over the nearby hills towards Fishguard before heading back home around lunchtime or early afternoon.

My most recent trip followed just this pattern. As usual the light here produced something special and it left me wishing I could share the experience. This wanting to share is a feeling I often get and as social media provides the perfect (and sometimes the only possible) means of doing this I have decided to post entries here at times.

I hope you enjoy them.

(There is a little more about the Preselis here https://jonjamesart.com/2020/10/07/the-preseli-hills/ )

Evening: Having nearly failed to persuade myself to make the effort and walk up to the rocks that evening, I was treated to a dramatic and rapidly developing sunset out towards St David’s and Ireland beyond, complete with Titian skies.

Morning: The following morning the air was rain-clean-sharp and bright with towering cumulus clouds,

which at one point looked like so many billow-sailed galleons heading into Newport bay,

and then sometimes a little more heavy and threatening.

The transformation this place can bring about often renders the world practically unrecognizable from what it seemed on first arrival and I am already looking forward to the next time.

Jon

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 1 MinuteEdit”Twenty four hours (or so) on the Preseli hills”

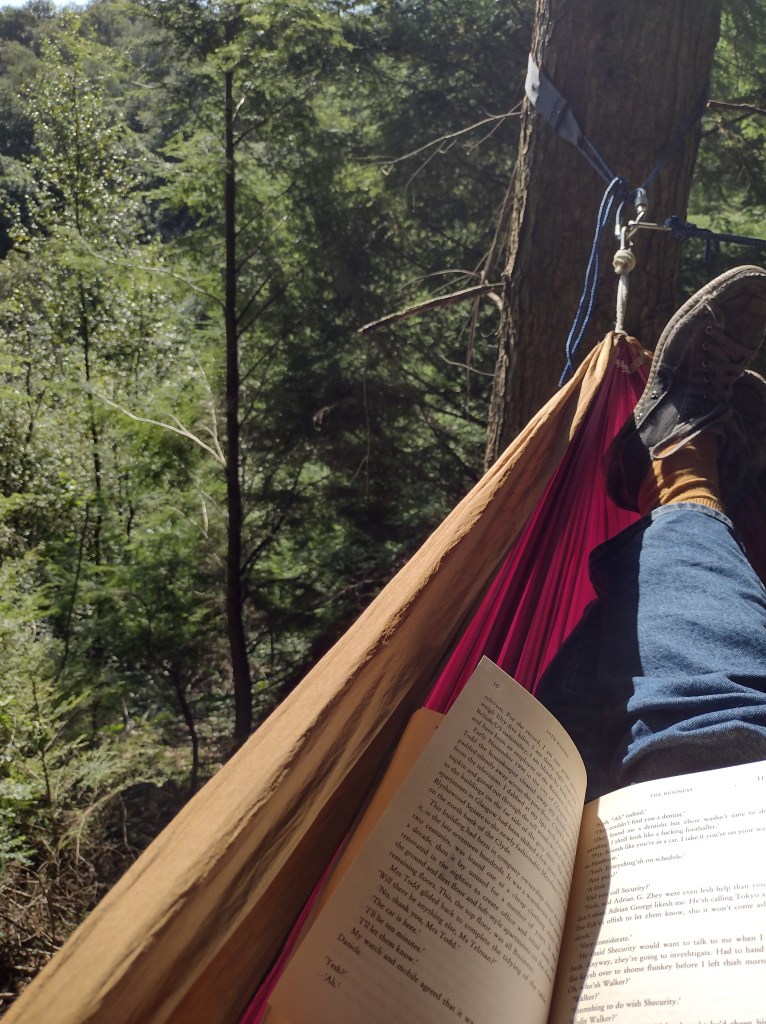

A place to read

29 August 2021

Today the buzzards are loud, mewing incessantly. I look up, but the conifers leave only small patches of sky visible between their feathery tops and the birds are hidden.

Their calling is met by the sound of the stream rising from the valley bottom, a hundred or so feet below me. The stream is also loud. It has been so for weeks now. It is loud because it is shallow, running and chattering over rocks; the water low at the end of a dry if not overly sunny summer. It will be loud again in the winter, but with a different voice, a voice born of rushing brown turbulence.

I am pleasantly suspended between these two sounds; the birds and the river. Suspended literally as well as metaphorically, on a seat slung between two trees halfway up the valley side.

To my right are conifers. Majestic. Two hundred feet tall or so. Western hemlock, planted maybe eighty years ago, native to northwest America but looking naturalized and attractive on this steep hillside. Conifers provide a poorer habitat than deciduous woodland, but these trees, I know, are enjoyed by the local marsh tits who harvest their cones. They were also visited last winter, I think, maybe, hopefully, by a pair of crossbills, although the birds were high and the identification difficult.

To my left is scrubby deciduous woodland; a mixture of hazel, oak, and beech; full of tawny owls and, in the summer months, chiffchafs, blackcaps and pied flycatchers.

The valley itself is a wooded gash in otherwise rolling county; as if a knife had been drawn across proved earth, leaving a cut which opened when the crust was baked. But in fact it was ice, not fire, that created this valley; melting ice draining away from beneath the glaciers of the last ice age, ten thousand or so years ago.

The particular trees I am suspended from are perched on a rocky outcrop twenty or so feet high. Coupled with the steep natural fall of the land this extra height is enough to allow me to see right across the valley and to lend my seat a certain vertiguousness, which I enjoy.

Today it is warm, still and quiet. There is little movement other than a gentle rain of pine needles from the branches above and the occasional flicker of white butterflies finding the sunnier patches of the woodland floor. But it is not always like this. Sat up here in a strong wind I have been in a mountainous sea, all green waves and movement; trees of different thicknesses finding their own resonances within the wind, bending and swaying, towards and away, each to a different time, like the violin bows of an amateur orchestra. The seat is attached to the trees, so you are in a boat on this sea rather than looking from the shore; there is even an edge of the sailor’s fear; what if a mast should break or a spar come crashing down.

But, so long as it is dry and not too cold, this is a wonderful place to sit and read. I know I am lucky to have access to it. Lucky to the extent even that guilt sometimes takes the edge even off the pleasure of reading.

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 2 MinutesEdit”A place to read”

Canal walk: Swallows

(During the summer of 2014, I got into the habit of walking the seven miles, along the canal, from Aynho warf to Cafe Nero in Banbury town centre for breakfast every Saturday morning. I remember the weather as being mostly perfect and these walks took on an unexpected magic and significance. This is one of a few of pieces of writing that came out them.)

15th April 2021

A few weeks into these walks it suddenly occurred to me that something was missing. It was summer but there were no swallows. Even over the canal, where you would expect flies to abound, there were none. But of course, we get used to this. The constant news of species decline. The degradation of the natural environment through pollution or ever-expanding housing, it goes on and on, oppressing and saddening. Perhaps, to an extent, we ignore this sort of news, and perhaps, to an extent, we are right to do so. Why shouldn’t we? We have, after all, to live in a world over which we have negligible control. We must ‘keep smiling’ and go on being at least reasonably effective in everyday life, so the ability to ignore bad news is maybe a necessary defence mechanism.

I was listening to the radio the other day, there was a discussion about the plastic pollution of our beaches and seas. How do we reconcile our romantic image of the sea with such news? The sea, a place of escape; fathomless and poetic, the realm of adventure and heroic deeds and of a refreshing otherness. How do we reconcile such feelings and images with the possibility that the seas are irreversibly polluted with plastic? I say ‘possiblity’ because I find it impossible to accept that the seas and the beaches are actually irreversibly polluted with plastic. PLASTIC! Of all the possible pollutants, plastic somehow seems the worse. Not only in a practical, scientific sense, because it does not break down, but also in a poetic or metaphorical sense. In plastic we have managed to unite images of cheapness and tackiness with immortality. By polluting the sea with plastic, we seem to have injected poison right into the heart of one of the most potent of life’s well-springs. The ‘idea’ of plastic seems to pollute the ‘idea’ of the sea in even more complex and harmful ways than real plastic pollutes the real sea.

This distinction of ‘ideas’ as a thing apart from their physical counterparts, seems interesting to me. Of course, at a mundane level it is inevitable; we can never know a physical object in its entirety and so we must always work with an abstraction of it. Such abstracted ideas, however, are often more complex and multi-dimensional than the thing itself. For example, our idea of the sea, as we have seen, is likely to be far more than just the sum of our scientific knowledge of it. It will include our personal and cultural associations at least. It is therefore not surprising that such an ‘idea’ has characteristics and behaviours which engender reactions far beyond those of the real object.

Mixing up the internal and subjective with the external and objective in this way is practically unavoidable. Even colour, which we cheerfully think of as a property of an external object, is, in truth, created entirely by our brains. The same being true of sound and the other sense impressions. The kingfisher, for example, is not blue and red, but colourless; the illusion of blue and red is created by our brains and projected onto the bird. We project not just sense perceptions such as colour and sound, but more complex phenomena such as feelings thoughts and emotions. To one person a sea bird colony appears a towering affirmation of chaotic but wonderful life, to another it is nothing but a smelly mess of squawking birds. Both are no doubt projecting some internal and probably unexamined element of themselves onto the external object. Even wilder or more abstract projections can be formed. We may look at nature and see love, or God, or a violent threat that needs to be subdued, or anything else for that matter, and because projection is often largely unconscious, we may feel such things to be objective reality; that the thing really has these properties, and be incredulous that others see things differently.

Is this good? Like a therapist’s patient, should we be encouraged to recognise these projections for what they are and ‘take them back’, relieving the objects of the burden of our expectations? Should we just allow the birds to be birds and the sea to just be the sea? Extremely easy to say, and maybe this is what science does; looks at what is left after we have withdrawn all our projections. And of course, it works. We sit back, in the large part, confidently expecting scientists to solve our problems, be they outbreaks of new diseases, global food shortages, or the development of biodegradable plastics and, with luck, we will not be disappointed. But there are difficulties and dangers here too. Science is brilliant at solving problems and generally improving life at a practical level, but the overall picture of existence it builds can seem bleak. To the extent that, for some, it is hard to live with.

This conflict between our subjective view of the world and what science tells us is not new. Perhaps the best-known expression was the romantic poet Keats’ accusing Isaac Newton of un-weaving the rainbow by explaining it in terms of prisms and the composition of light.

Is there an analogy here? One of the guidelines for building cages, or should I say enclosures, in modern zoos is that they should be such that the captive animal is able to ‘express its natural behaviour’. Birds should be able to fly, monkeys to climb and, presumably, hippos to wallow. Is one of the problems with science that it seems too bare a cage; a concrete rectangle maybe, in which our need for nutrition and air is recognised, but with no facility for us to express our imaginative, meaning-hungry natures?

I don’t know. Sometimes it seems like this to me, and that, to change metaphor, scientists are like miners; in that they go down to a dark and inhospitable place to bring back substances of practical use to us all. At other times the contrary seems true, and I would agree with the physicist Richard Feynman when he said that (to paraphrase); to think that science in some way undermines aesthetic sense is ‘a little bit nutty’.

Attempting to reconcile these viewpoints seems simultaneously interesting, difficult, and important. But this is the good thing about walking, it gives you time to think about such things.

Regarding the swallows (and maybe we can hope it will be the same with plastic) it was not as bad as it might have been. A week or so later, I was walking up to the lock gates at Kings Sutton and there they were, low over the water, twisting swooping and diving, with that characteristic pattern of flight which seems to have been laid down in our consciousness over a lifetime of summers. Slender wings the colour of mussel-shells or summer twilight and under the chin the hint of summer warmth and of the autumn to come. Coincidentally, just as I saw them, the lock gates above which they were flying were opened and for a moment it felt as both the emotional release of seeing the swallows and the water released by the lock gates flooded out together over the countryside.

Swallow The gap is joined The spark flies The lock above the old bridge opens Summer floods The swallow has made the cut

(‘cut’ is a country name for canal)

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 5 MinutesEdit”Canal walk: Swallows”

Living light

23rd March 2021

This blog is about a form of bioluminescence known variously as ‘sea sparkle’, ‘milky sea’ or more poetically ‘mareel’, which is a Shetlandic name meaning ‘sea fire’, (from Old Norse marr (“sea”) + eldr (“fire”). Also “miracle”, “morrali”, “glimro”)

A near miss:

I feel greedy, wanting to see sea sparkle. The sea provides us already with seemingly inexhaustible inspiration and possibility; to want it to also put on a light show seems ungrateful. I must admit though, since I first read descriptions of night-time glowing seas, I have wanted to see them for myself.

I got quite close once. I was ‘crewing’ for the first leg (Eastbourne to Falmouth), of a sailing trip that was going to cross the Bay of Biscay, carry on down to north Africa and eventually cross the Atlantic. The skipper was to pick up different crew for the various stages and on this first leg it was myself, a friend, my father-in-law, and a young vivacious eastern European girl whom none of us had met before called Lenka1.

This was to be my first time sailing at night and I was full of romantic expectation of seeing the mast ‘stir a sky full of stars’, the ‘loom’ of the lighthouses we would pass and maybe even sea sparkle. However, although we had good wind and a fast trip2 none of this happened. The sky was overcast, and the veiled moon and shore lights reflecting from the clouds prevented it from ever getting properly dark. There was not a star to be seen and certainly no glowing seas. With a strong north wind and a rough sea, it was also extremely cold and uncomfortable3.

We arrived in Falmouth tired and the three of us were relieved to climb into the warmth and comfort of a modern car and head for home.

Lenka was staying on for the next leg and, after a day recovering, was to be joined by two new crew members for the trip across Biscay. We swapped email addresses so we could keep track of how the rest of the journey went and said goodbye.

A couple of days later a wonderfully joyous email arrived in my inbox. High on tiredness and excitement, writing from the plane on the way back from Spain, Lenka described, in ecstatic broken English, how they had met not only bad weather and rough conditions but large areas of sea sparkle4. As the boat had ploughed into each glowing wave, cascades of glimmering sea spray had been fired back over the deck, drenching the crew, who, excited and laughing, had also begun to glow. Lenka described how the luminous water had run into their eyes, and mouths, picking them out and making them shine with sea fire.

As you might guess, I was sorry not to have been a part of this; to be aboard a boat sailing through a spectral sea with a maniacally laughing and glowing crew is something you will not get to do every day.

While I am unlikely to get the chance of experiencing sea sparkle in quite such dramatic circumstances I would still like to see it. I have therefore made these few notes, partly out of curiosity and partly in the hope of increasing my (and anyone else who is interested) chances of seeing it in the future.

What is sea sparkle:

Nature has learned, through the guided play of evolution, to perform various tricks with light. Some of these modify light present in the environment, while with others generate ‘new’ light. The bright blue flash of a kingfisher, the shimmer of certain butterflies’ wings or the rays of the blue-rayed limpet5 are all examples of a phenomenon known as iridescence, in which the microscopic structure of the wing, feather or shell modifies the light falling on them, and causes them to shine and shimmer. Although iridescence generates no new light the effect can be surprisingly bright; catch the sun on the back of a kingfisher as it flies low over a river and you would think it was lit from within.

Bioluminescent creatures on the other hand generate light and hence shine or glow in the dark.

Instinctively, forgetting science for a moment, the ability to produce light seems to be somehow miraculous. There is something elemental about light. It seems more than just another physical phenomenon. Light and its counterpoint darkness are a primeval pair of opposites. ‘Let there be light’, the ‘light of reason’ and the ‘dark ages’, the ‘glimmer of consciousness’, the depiction of holy people as having haloes and the very word ‘enlightenment’, all contain light at their core. In children’s books as well, the ability to generate light is depicted as magical and firmly in the domain of wizards or supernatural beings, such as Harry Potter, Gandalf, Ged8 or ET.

Such connotations seem to give light, and the ability to generate it, a mystical or even spiritual aspect6,7.

However, despite all this, being able to generate light through bioluminescence, is in fact very natural and commonplace. Many, many creatures, especially marine creatures, bioluminesce and it is thought that nature has reinvented bioluminescence fifty or so times during the course of evolution. The tree of life is, like a Christmas tree, decorated with many twinkling and flashing lights.

The bioluminescent creature responsible for sea sparkle is a tiny single celled organism that drifts around the oceans as a component of plankton. It has the pretty Latin name ‘Noctiluca scintillans’, which translates as ‘sparkling night light’.

Undisturbed Noctiluca produces an extremely pale glow that is hard to see, but this changes if the water is disturbed by wave action or by someone walking or swimming. The cells then flash and sparkle with a blue-green light9 as a defence mechanism, to put predators off feeding, or to attract larger predators which will, in turn, feed on the predators of Noctiluca10.

The mechanism by which bioluminescence is generated is chemical and is similar across many bioluminescent species. It involves an enzyme called Luciferase, and a light emitting compound called Luciferin12,13. In sea sparkle the Luciferase-Luciferin reaction is stimulated when the shape of the cell is distorted by the forces within the disturbed water. I have read that cells only sparkle at night and that even if you take a jar of sea water containing sea sparkle into a dark room it will not sparkle unless it is also night-time. It seems from this that although only a single cell Noctlluca must contain an internal clock, (but then you wonder if they also take account of the different lengths of night and day in winter and summer in which case, they also need to keep track of the time of year as well as the time of day).

Finding sea sparkle

To be able to see sea sparkle it is necessary for Noctiluca to be present in large numbers; the conditions for this to occur therefore provide a guide for when it might be best to go hunting for it.

These conditions include:

- Warmth: Noctiluca reproduces more readily in warm water, so looking after periods of warm weather might be a good idea.

- Shelter: Sheltered, calm bays are good hunting grounds as here the plankton stay near the surface of the water rather than becoming distributed throughout its depth.

- Onshore breeze: A gentle onshore breeze may also help as this will push the surface water containing the creatures toward the shore.

Even under these conditions I get the impression that the appearance of sea sparkle is quite erratic and unpredictable. There are, however, various internet groups dedicated to reporting sightings, including one dedicated to sightings around the Welsh coast14. Keeping an eye on such sites could significantly increase the chances of catching this elusive phenomenon.

If you go hunting, good luck!

Notes:

- Not her real name.

- Approx. 280 miles in 34 sailing hours (8.3 knots approx. average).

- It is one of the strange things about sailing that despite uncomfortable experiences like this it draws you back time and again.

- I do not know how large the areas Lenka sailed through were, but I have read that sea sparkle can cover thousands of square miles and be visible from space.

- There is a short blog I wrote about Blue-rayed limpets here.

- It seems to me a particularly charming aspect of bioluminescence that it is what might be considered more lowly creatures, such as glow worms, fireflies, jellyfish, and single celled plankton drifting on sea currents, that have the ability generate light, while the ‘higher’ mammals, including man, are denied it.

- This aspect was nicely brought out in the Disney film ‘Avatar’ in which the fantasy world of Pandora was lush with bioluminescent plants and creatures.

- Ged was a wizard in Ursula le Guinn’s excellent Earthsea Trilogy (which included the original school of wizardry on ‘Roke Island’).

- This shade of blue-green light is the best colour for penetrating sea water, (the colour of the rays of the blue rayed limpet is a similar shade, for the same reason).

- It is easy, when casually browsing on the internet, to get the impression that such interpretations are established facts – but other sources indicate that such ideas are just hypothesis and that research in many areas is still ongoing.

- Screen capture from full video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bJcTWr8-mFo

- This is the subject of research inspired both by curiosity and the search for possible practical applications. The American university MIT are looking into the possibility of engineering bioluminescent plants to replace electrical lighting ( https://news.mit.edu/2017/engineers-create-nanobionic-plants-that-glow-1213 )

- ‘Lucifer’ is Latin for ‘bringer of light’.

- For example, https://seasparkle.wales

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 7 MinutesEdit”Living light”

Danger barnacles!

8th February 2021

Due to lock down I have been unable to get to the beach for a while and so this blog is based on some photographs I took on an earlier visit and some bookwork. It is about barnacles.

Barnacles (Latin name Cirripedia) are those tiny, ivory coloured, volcano shaped shells you see attached, often in large numbers, to rocks along the shore. Each is only a few millimetres across, but their numbers can be as the stars in the sky, colouring the rocks and becoming part of the landscape. I like them if that is not a silly thing to say. I am not quite sure why. They seem more like a form of rock than a form of life; hard, immovable, and apparently inert, yet as much a part of the shore as the sea and the sand.

Barnacles (and a few limpets) encrusting rocks in the intertidal zone.

Although they may appear featureless, get down on your knees and really look, perhaps with a magnifying glass, and you will see there is more to them than you might have thought. Each shell is made up of several plates1 that form a small chamber, though often the plates are fused together and the joints hard to see. The chamber has a flat top which is closed by more plates making a pair of tiny gates. These gates meet along an intricate wiggly line which looks a little mysterious, almost as if the gates are sealed with a hieroglyph or magic symbol.

But these gates do not need a spell to open them, just a covering of sea water. When the tide is out and the barnacle is above water the gates shut, providing protection from predators and preventing the creature inside drying out, but when submerged the gates open, allowing the barnacle to feed by extending a number of feathered legs called cirri which capture tiny particles of plankton suspended in the sea water.

If you look carefully at different groups of barnacles up and down the shore you may find some that look subtly different; particularly the detailed shape of the plates and the line along which the gates meet. This might be because you are looking at a different species of barnacle, however barnacle identification is not easy, and you will need to look closely.

Two different species of barnacle. Left: Semibalanoides balanoides, Right: Chthalamus montagui (I think!)

But be careful! Even as you crouch down to look you should know that you are potentially in danger and that although small and apparently lifeless, barnacles can be hazardous. It is a well documented fact that at least one fully grown man was trapped and held captive by barnacles, not for a few minutes, but for a full eight years.

This man was Charles Darwin, the world-famous scientist and author of ‘The Origin of Species’ who, having found an unusual type of barnacle while voyaging on the Beagle thought he would spend ‘some months, perhaps a year’ 2 sorting out the then chaotic classification of the world’s barnacle species. Six years and many hundreds of pages of detailed scientific publication later he would write, to a friend (with still two years’ work to go):

“I am at work on the second vol. of the Cirripedia, of which creatures I am wonderfully tired: I hate a Barnacle as no man ever did before, not even a Sailor in a slow-sailing ship”.3,4

So, what is this creature that can engage such a brilliant and hardworking mind for eight years? What exactly is a barnacle?

Even before Darwin gave them his attention it had taken science quite a long time to decide what barnacles are and what class of animal they belong to. Maybe we can see why. At a casual glance barnacles look like tiny limpets, which also have hard, roughly conical shells and, at the times we generally see them are stationary and appear rigidly attached to the rocks. Barnacles and limpets however are completely different types of animal; limpets are molluscs, which are creatures like snails, that have soft unsegmented bodies, whereas barnacles have a segmented body and a hard exoskeleton. Even so barnacles were classified as a type of mollusc until it was discovered that they pass through two free-swimming larval stages5 before they permanently attach to the rocks. It was the observation of these larval stages that led to the correct classification of barnacles in 1834, as belonging to Crustacea, the same grouping as crabs, shrimps and lobsters.

There are two main categories of barnacle, the type we have been talking about, which attach directly to the rocks and are known as sessile barnacles and a type that attach via a stalk, which are known as pedunculate barnacles. There are over a thousand species of barnacle worldwide but around the UK we have just two or three species of pedunculate barnacles, which are usually found washed ashore attached to floating driftwood or plastics and, depending on whether you count invasive species or not, six or nine species of sessile barnacle. However, differentiating even such small numbers of species can be tricky. In the words of Charles Darwin again:

“Whoever attempts to make out from external characters alone, without disarticulating the valves [Darwin called the shell plates valves], the species, (even those inhabiting one very confined region, for instance the shores of Great Britain) will almost certainly fall into many errors”6

The difficulty seems to arise because there is a large variation in the appearance of individual barnacles, even within one species. Books such as ‘A Student’s Guide to the Seashore’7 offer a step through guide to barnacle identification, but as alluded to by Darwin, differentiating between some species requires scraping the barnacle off the rock and dismantling it. Personally, I think I would rather live with a little ambiguity in my identifications.

If we think classifying barnacles as molluscs was something of a scientific blunder it is as nothing to what was believed in the middle ages about a type of pedunculate barnacle known as a goose barnacle. This type of barnacle, which was found washed up on British shores attached to driftwood, was thought to be the embryo of a black and white goose known as a barnacle goose. Because this goose only winters in the UK it was never seen to breed and as migration was not understood at that time an explanation for its seasonal appearance was lacking. The shape and colour of the floating goose barnacle looks, if you have a good imagination, somewhat like the beak, head, and neck of the goose and so the one was assumed to be the embryo of the other. The full supposed life cycle involved a barnacle goose tree (remember the barnacles were always found attached to wood), on which the goose barnacles grew and from which the geese hatched.

One form of the wonderful barnacle goose tree8.

There is an Anglo Saxon riddle that accompanies this story:

My beak was close fettered, the currents of ocean,

running cold beneath me. There I grew in the sea,

my body close to the moving wood.

I was all alive when I came from the water,

clad all in black, but a part of me white.

When living, the air lifted me up,

the wind from the wave, and bore me afar,

up over the seal’s bath. Tell me my name9.

I have to say, I find this an attractive story and sometimes wonder if it might not have been fun to have lived in less scientifically constrained times, when one could be free to entertain poetic ideas like geese hatching from barnacle trees. But then maybe there is a poetry of a different and more powerful sort in the image of a man working patiently for eight years to understand these tiny creatures, while all the time devising the theory that would explain the growth, not of the barnacle tree, but of another tree, the evolutionary tree of life, among the branches of which not only barnacles and geese but man and all other creatures would be shown to have their place.

Notes:

- Some UK species of barnacle have four plates, and some have six.

- Letter to: J. D. Hooker [2 October 1846]

- Letter to: W. D. Fox, [24 October 1852]

- This and other wonderful excerpts from Darwin’s letters at: https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/darwins-bad-days

- Observations of the ‘naupliar’ and nonfeeding ‘cypris’ stages of the barnacle’s life cycle were published in 1830 by the British military surgeon and marine biologist John Vaughan Thompson.

- From: A Monograph on the Cirripedia, by Charles Darwin, London: Ray Society, 1854.

- ‘A Student’s Guide to the Seashore.’ J. D. Fish & S. Fish (Third Edition) (301-311)

- From Topographia Hibernica British Library MS 13 B VIII Ray Oaks, CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

- Anglo-Saxon Riddles of the Exeter Book (1963) translated by Paull Franklin Baum (Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License)

Jon James Uncategorized 1 Comment 6 MinutesEdit”Danger barnacles!”

Searching the shore

I am no biologist, and I don’t really know very much about shore life. Before retiring and moving to be near the sea I worked in physics and engineering. The attractions of the sea were for me, like most people I would think, a mixture of fresh air, the simple pleasures of sun, sand and sea on skin and the novelty of a different environment. But the coast has also always inspired. I used to walk along the shore and use the sea and sand to spark thoughts about physics. Actual physics, such as wondering how sand ripples form or more esoteric metaphysical thoughts, inspired by the sea, about the universe or time and space. Biology was never my thing, a bit too squishy and potentially messy for my liking and, I thought, less fundamental and therefore intrinsically less interesting than the big questions of physics.

Bird watching was the nearest I came to an interest in life sciences. I had often thought that once retired and settled in, I would look for some ornithologically themed volunteer work. I imagined myself monitoring bird numbers along some stretch of wild Pembrokeshire coast. Motivation for a regular walk and a chance to feel like I was doing something useful in the face of the constant soul-destroying news of climate change, pollution, habitat loss and declining wildlife.

It was my son who noticed the online advert for volunteers for Living Seas Wales (https://livingseas.wales/ ) and passed it to me. Not birds, but the life of the seashore. Recording what is present, but also looking for invasive species or species indicative of climate change.

The novelty intuitively appealed. The chance to learn something new. Not just new, but quite different. The sea, an unknown alien world to most of us, is particularly good at firing our imaginations and I enjoyed the thought of immersing myself in this new subject. I made contact and after a pleasantly small amount of admin and some online training, was ready to go.

Since discovering it a few years ago I have greatly enjoyed the area around Dinas Island on the north Pembrokeshire coast. The walk around the head itself is beautiful and dramatic with views out into Cardigan bay and across to North Wales. There is even a small sea stack which, in the spring and summer, hosts colonies of beautiful, raucous seabirds including razorbills and guillemots.

Razorbills and guillemots on Needle Rock, Dinas Island

It was maybe natural then that I would choose a bay near the Head for my first shore search.

Picking a pleasant day, I arrived a little before low tide. It was easy this first time. I knew nothing and so everything was new. I thought the easiest thing might be just to take photographs and identify what I found back at home with books and the internet to hand. I walked over the sand, heading to the rocks that form one side of the bay, photographing the different seaweeds that were either growing on rocks or cast up on the sand as I went.

I like the early stages of getting into a new subject. It reminds me of looking out onto a field of newly fallen snow. You have no preconceptions or mental clutter and are free to wander where you will, think what you like and ask whatever questions come to mind. I remember wondering whether seashore life is as seasonal as life on the land and whether the types of rocks, or how exposed a shore is, has much effect on what will be found there. I also had more specific questions such as whether those little fish you sometimes find in rock pools choose to live there or just get stranded as the tide goes out and if a rock pool is simply a visible bit of the undersea habitat that lies all around or a fundamentally different and unique eco-system.

Arriving at the east end of the bay I chose a moderately sized, attractive looking rock pool and knelt for a closer look.

Rockpool

It is a cliché I know, but rock pools do look like gardens. Some look like flower gardens, full of life and colour, others are more like Japanese Zen gardens, austere arrangements of rock and light and shade. This one was of the first type, a play of weeds of different shapes and colours; greens and reddy-browns, flat, and feathery, with the rock basin below the water line covered in that pale pink growth you sometimes see; a type of under-water lichen perhaps?

There were a number of those sea anemones that look, when they are closed, like blobs of red jelly, as well as shells of various sorts, some I recognised as limpets but others I was not sure about. I took photos of all these before spotting something more unusual; a broad piece of brown seaweed covered in a fine geometric pattern. I had no idea what this was. More photographs.

I was just about to move on when I became aware of a small patch of pale star-like growth, partially hidden among the weed on the bottom of the pool. As my eyes tuned in, I realized there was quite a lot of it, perhaps it was another type of anemone.

A quick look around, followed by a cup of coffee sat on a rock and a short, shouted conversation about the pleasantness of the morning with a fisherman setting out to pick up lobster pots and it was time to go. It had been good. There is something about going to a place with a sense of purpose rather than just strolling along looking at the view. You engage with things more deeply, people come up and talk to you, interested in what you are doing.

My lasting impression was just how much life there had been. Fifteen species1 within a few square yards, some of which I had never seen before and had not known existed. Seashore life is not cosy or cute, but it is beautiful and wonderfully alien. You might as well be exploring life on other planets, Star Trek style, as delving into rock pools. Getting to know the shore is bringing home to me that Life is at least as great a mystery as the abstract questions of physics and of course, you only have to look up and the birds are there as well.

A few of the species described above (tentative ID):

- As of now (January 2021) this total is now 28. I have an on-going photo-record at: https://jonjamesart.com/shore-search/

Jon James Uncategorized Leave a comment 5 MinutesEdit”Searching the shore”

Philosophy of Mind

4th January 2021

I recently completed an Oxford University short course on Philosophy of Mind. This is an area I have interested in (or maybe I should say tormented by) for a long time.

I would like to write some more on this at some point, but for the moment I have just copied the final essay of the course below. Probably it wont be of interest to anyone, but I feel it might as well go here as anywhere, or nowhere.

Can one reasonably be a dualist in this day and age?